Sustainable infrastructure development is expected to improve human well-being while avoiding or reducing the impacts on the physical and natural environment. In other words, ensuring the viable coexistence of biodiversity, ecosystem processes, and human activities. In landscape management terms, this means the transport infrastructure life cycle is part of landscape dynamics driven by natural and human processes. Embedding transport infrastructure into the landscape needs to deploy landscape design techniques based on the description and analysis of:

- The geophysical environment including the biodiversity and ecosystems processes.

- The socio-cultural environment.

- The subjective sensorial environment (or how people living or passing through the landscape perceive it with all their senses).

This holistic and systemic management of territories, often called the socio-ecological approach, is rarely adopted during the transport infrastructure life cycle management and should be encouraged (see Chapter 2 – Policy, strategy and planning).

Historical and cultural context as well as social dynamics must be considered during the design of transport infrastructure. Landscape history leads to socio-cultural dynamics that can be highly specific for a given territory. Moreover, the existing transport networks are a result of history over centuries and this history must be considered during infrastructure design, upgrade or adaptation. In other words, inclusive transport infrastructure planning and design are expected to consider and adapt to the socio-cultural dynamics of the territories where they are to be located. Techniques from social sciences such as questionnaires, interviews, audit, and stakeholder mapping, amongst others, should be implemented to understand the past and present socio-cultural dynamics. These types of assessments are of prime interest to ensure the dynamic continuity of landscapes as well as to detect and anticipate social conflicts before they happen and improve the engagement of local communities in the project.

Linking international and national targets with the European Landscape Convention

The European Landscape Convention, ratified by 40 countries, aims to provide a common vision of the landscape at EU level. It encourages parties to establish and implement cultural, environmental, agricultural, social and economic policies aimed at landscape protection, management, and planning. However, both the Convention and the regulatory tools that emerge from it mainly focus on the social aspect of the landscape including its aesthetics, strongly highlighting the preservation of the perceptual aspect of the landscape. Transport infrastructures are in the scope of the Convention. However, biodiversity is not prioritised as ecological dynamics are not explicitly targeted. Embedding transport infrastructure into the landscape requires the integration of biodiversity dynamics using landscape management approaches.

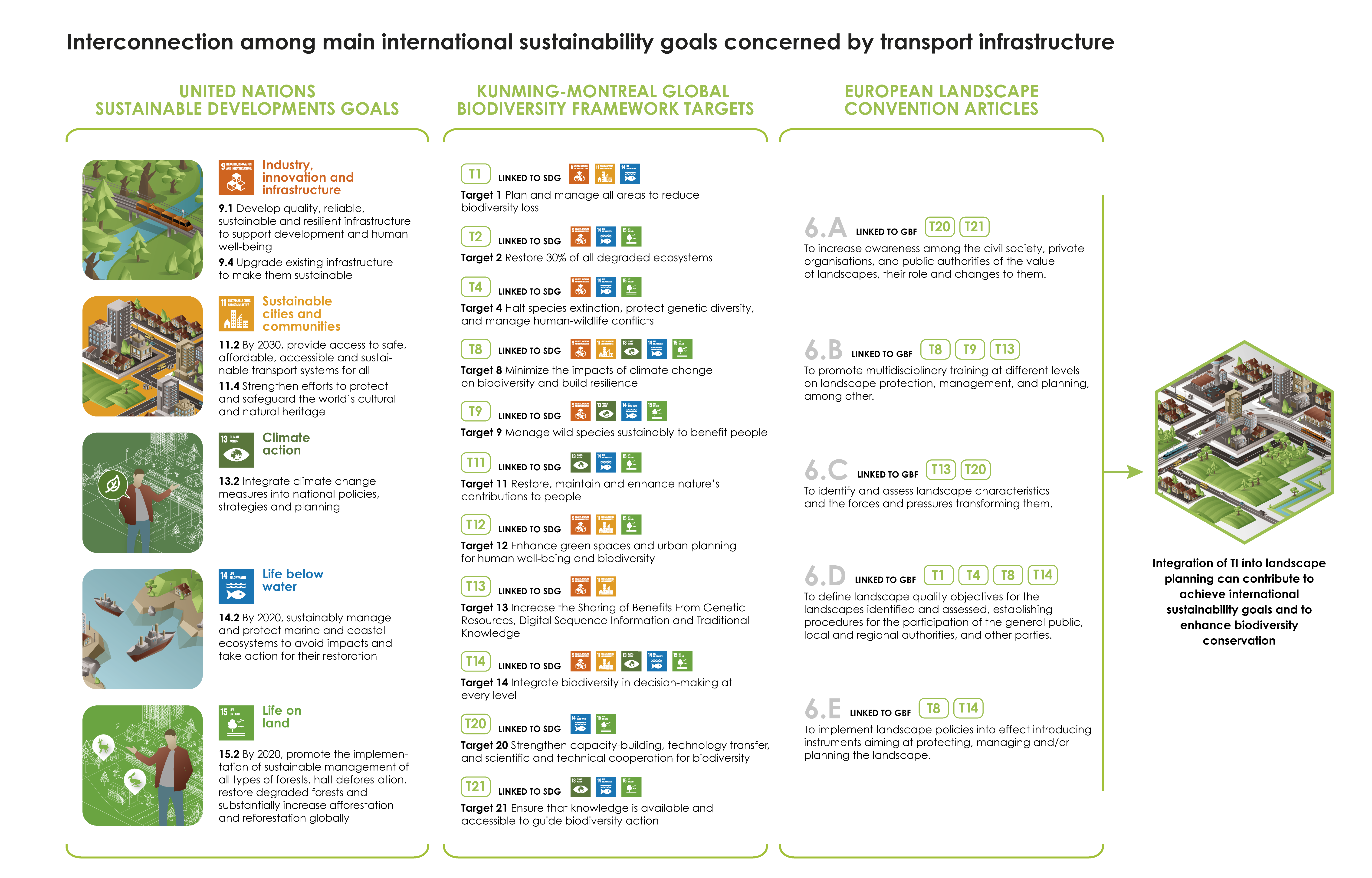

Taking a systemic and holistic approach at landscape scale can also contribute to the achievement of international and national conservation targets. In December 2022, Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity agreed the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), with its vision of living in harmony with nature by 2050. The GBF includes four goals for 2050, supported by 23 global targets to be achieved by 2030. It is an inclusive framework requiring action throughout government and society. Similarly, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) have also been agreed by countries to end poverty, ensure biodiversity protection, and peace and prosperity for all. Governments and the private sector are expected to create and implement policies, plans, and programmes that align with GBF targets and SDG goals.

For example, a framework can be designed in a way that it allows governments and infrastructure developers to consider different SDG and GBF targets (Figure 4.1.1). Following this framework, the sustainability of existing and future infrastructure can be improved through integrated planning and participatory approaches. By taking this approach the upgrading of existing infrastructure or development of new projects can have positive consequences for conservation, by either reducing the impacts of the infrastructure or maximising the ecological gains and implementation of compensation measures.

At a national level, infrastructure planning can be integrated within strategic documents that deal with planning at large geographical scale (see Chapter 2 – Policy, strategy and planning). These planning approaches can be useful in balancing developments associated to transport infrastructure and other human-related activities with environmental, sociological, and historical issues. However, these approaches must also deal with the wide variety of factors within the different scales of development and existing strategies (e.g., local environmental assessment and regional strategies).

In conclusion, the spatial planning process, provided by infrastructure development, is an excellent opportunity for stakeholders from different sectors and at different scales to share and consider each others’ issues. These exchanges can only be implemented if the process is designed to be participatory and implemented across a broad range of actors. In addition, the landscape object and scale are very suitable to understand the dynamics of biodiversity and to act to protect it, both for conservation programmes and for planning mitigation measures (see Chapter 3 – The mitigation hierarchy). The landscape scale allows a better understanding of transport infrastructure impacts on local biodiversity as well as the impact of socio-economic and cultural changes brought about by these infrastructures. This working scale also provides emerging opportunities for large scale biodiversity-based economic activities which are expected to support the sustainability of landscape management in the long term. Such opportunities are described in the following section.

Emerging opportunities based on territorial economy approaches

Territorial economy consists of transforming territorial issues related to economic and demographic development into opportunities for creating new trajectories of development based on specifics of a territory and the construction (or consideration) of new resources.

At the landscape scale, transport infrastructure should be considered as a crucial element in the territorial economy which contribute to the structure of physical space and local economic dynamics, thus creating interactions with other economic sectors. For example, transport infrastructure development:

- Can support the energy transition of territories with a co-evolution of traditional electricity grid systems towards a redeployment of energy production modes and transport networks following transport infrastructure alignment. In these cases cumulative impacts need to be carefully evaluated (see Chapter 1 – Ecological effects of infrastructure).

- Should be coordinated with mobility planning at a territorial scale. The development of large-scale transport infrastructure must be anticipated in line with communities and users, providing an opportunity to transform their network of mobility.

- Should be an opportunity to link actors and issues in a given territory. This coordination can be managed with the use of smart cities approaches which provide benefits to local communities and initiate their ecological transition through a change in practices.

When planned at a landscape and territorial scales, transport infrastructure can provide opportunities to change or enhance connections between many different sectors, developing local economies and creating innovative strategies.

In this context, infrastructure managers and operators play an important role in enhancing the contribution of infrastructure to the territory by applying innovative Nature-based Solutions (NbS) and other best practices, which contribute to nature conservation and also to overcome the current major challenges posed by sustainable development. As transport infrastructure development is first and foremost a source of impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services, business models around it are primarily concerned with two strategic notions:

- The application of the mitigation hierarchy at a project and landscape level (from a regulatory or a voluntary perspective) (see Chapter 3 – The mitigation hierarchy).

- The integration of transport infrastructure into a territorial economy approach based on environmental assets.

The sections below describe important considerations when applying a territorial economy approach.

Enhancing and scaling-up of biodiversity solutions

Evaluation of the relevance and efficiency of actions to mitigate impacts of infrastructure on biodiversity and to enhance biodiversity conservation and restoration could be undertaken at landscape scale. Some examples are the development of wildlife passages or actions to reduce pollution and other impacts to adjacent land. These measures could also support the deployment of labels and/or certification or the development of new activity sectors led by transport infrastructure managers through examples such as:

- Development of new biodiversity indicators.

- Implementation of contracts to develop actions which benefit biodiversity in Habitats-related to Transport Infrastructure (HTI) (see Chapter 5 – Solutions to mitigate impacts and benefit nature. Habitat-related to transport infrastructure (HTI) management).

- Development of strategies for the acquisition of areas by transport infrastructure managers to develop new mechanisms which contribute to mitigating climate change (carbon sequestration, for example).

Application of innovative landscape management strategies through nature conservation and restoration or even a free natural evolution by applying ecological management.

Integrated management of territories through the ecosystem services approach

To harmonise biodiversity and ecosystem services with transport infrastructure, the analysis of the landscape structure to reduce risks (e.g., flood control, protection against falling rocks, etc.) can serve the purpose of enhancing management practices and develop new approaches towards transport infrastructure integration in the landscape. These practices through disciplines such as risk management, ecology, geography and socio-economic evaluation, might serve to develop new solutions aimed at improving the contribution of pre-existing ecosystems to the transport infrastructure and the rest of the ecological, economic and social interests at a landscape scale.

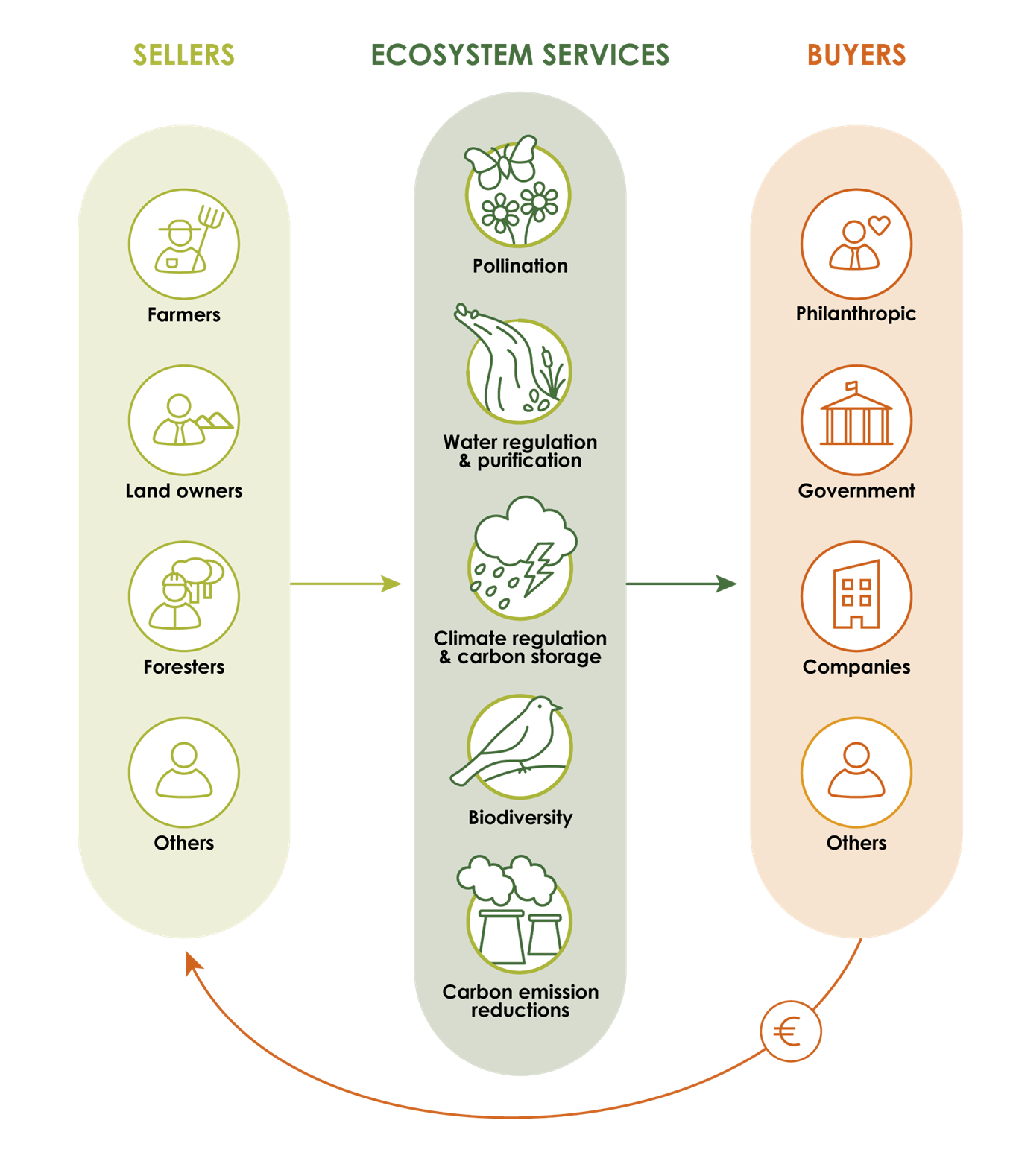

Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES)

PES is a voluntary transaction where a well-defined ecosystem service or a land use that provides that service is ‘purchased’ by one or more buyers, from one or multiple service providers on the condition that the provider delivers the ecosystem service (Figure 4.1.2). These arrangements bring together the beneficiaries or users of ecosystem services, both public or private, and stakeholders such as land managers, farmers and foresters in a position to influence the quality or quantity of these ecosystem services. Stakeholders are then able to quantify and measure the progress made in terms of environmental conditions. For example, at a catchment scale, there could be different activities potentially impacting water quality through land use changes that impact on natural filtration and purification of the soil. The PES scheme makes it possible to remunerate landowners in the catchment area to balance the potential economic benefits of the activities that would affect water quality, reducing the impacts on water resources and ultimately improve water quality. These agreements should be subject to contracts between the different parties, which may include public and private enterprises, local authorities and landowners.

Nature-based Solutions (NbS)

The quantity of impacts on nature generated by economic activities calls for a paradigm shift and deep transformative changes which can be addressed through both technological solutions and Nature-based Solution (NbS) based on biodiversity and ecological processes at the landscape scale. NbS can generate multiple positive impacts on climate, society and economy. They can also promote synergies between biodiversity, a local range of ecosystem services, the sustainability and resilience of transport infrastructure and the health and well-being of local populations by, for example:

- Enhancing resilience of transport infrastructure and local ecosystems to climate change.

- Contributing to climate change mitigation by reducing the carbon footprint of the infrastructure, reducing emissions and sequestrating carbon.

- Providing benefits for biodiversity, reducing impacts and improving habitat quality.

- Providing ecosystem services which improve air, soil and water quality.

Promoting local development by providing sustainable livelihoods and protecting local heritage and culture.

Circular economy solutions

The three traditional principles of the circular economy: Reduce; Reuse; Recycle can be applied in the transport infrastructure landscape approach by:

- applying the mitigation hierarchy (see Chapter 3 – The mitigation hierarchy);

- reconsidering the role of some transport infrastructure at a landscape scale to face or anticipate issues in a circular economy approach such as:

- the end of infrastructure’s life cycle and its decommission allowing to define other uses including restoring nature;

- the unsuitability of the infrastructure considering environmental challenges in terms of social choices (change in habits, ecological planning, mobility planning) or in terms of physical exposure to climate-related hazards and its recycling (process of deconstruction for example);

- creating new responsibilities towards the environment for infrastructure managers, such as a need to anticipate future regulatory changes in terms of land-use.

Corporate sustainability frameworks

The emergence of frameworks such as the Science Based Targets Network (SBTN) implies that economic actors have to play their part in halting biodiversity loss while improving business performance. SBTN aims to help companies define, implement and monitor their path to nature commitments through setting science-based targets. The five steps towards action proposed by SBTN are: Assess; Interpret and Prioritise; Measure; Set and Disclose; Act and Track. A number of businesses are already piloting the SBTN approach and developing tools to assess their impacts and reliance on nature setting targets, monitoring their progress and implementing transformative change.

Transport infrastructure managers and companies will certainly benefit from the testing and implementation of the SBTN model, as the business model governing their operations is just as reliance on biodiversity on a landscape scale as it is currently damaging to it.

In parallel, new reporting frameworks for business have increased the push for transparency to disclose publicly what impacts are being generated and how they are being managed and acted upon. For example, the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) which is a government-supported global initiative that proposes a set of disclosure recommendations and guidance to report and act on nature reliance, impacts, risks and opportunities. In January 2024, 320 companies committed to be early adopters of TNFD recommendations.

The current regulatory context in the EU already plays a major role in relation to the elements below:

- The EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) which is framing Environmental Social and Governance reporting for companies that have over 250 workers.

- The implementation of the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) which increases transparency on how financial market participants and financial advisers integrate sustainability risks into their investment decisions.

Finally, ecosystem methodologies focused on ecological accounting allow economic actors to consider the quantity of impacts they have on ecosystems and to integrate the costs of protection and/or restoration needed into the accounts. While adopting this accounting system represents a major change in how businesses are managed, it can play a strategic role in the ability of transport infrastructure managers to integrate their infrastructure projects into the landscape.